Self Diagnosis

We've been self-diagnosing medical issues online for two decades now. Doctors tell us not to, but we do it anyway. Today we ask ChatGPT, before that Google, but twenty years ago we clicked on body parts in the WebMD symptom checker. The technology changes, but the behavior remains the same. Here's a journey back to a little feature I helped build one iteration of that stood the test of time.

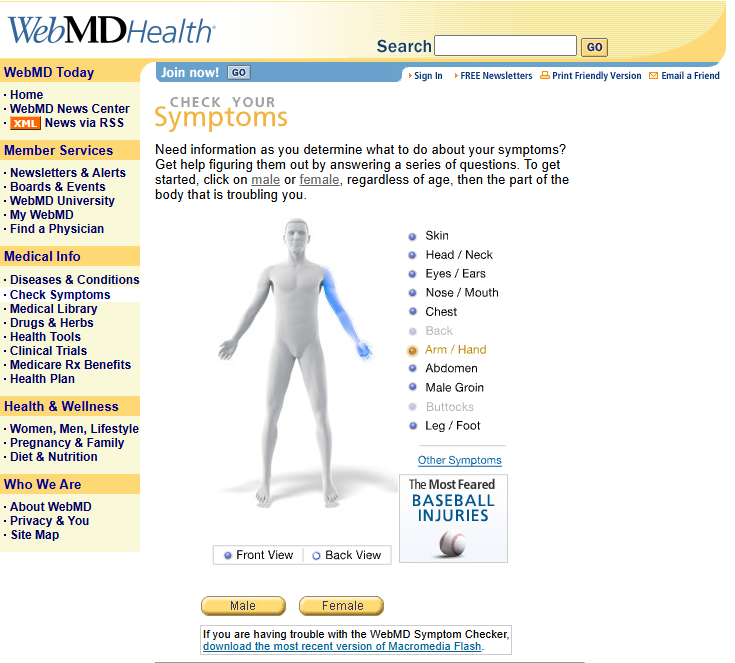

In 2005, WebMD had just released the Symptom Checker. It was built in Flash—smooth, interactive, and visually polished. Users could click on body parts to identify symptoms, and it worked beautifully.

But Flash had problems: it required a plugin which many users didn't have, or couldn't figure out how to download, especially bad for WebMD's target demographic. Soon after the Symptom Checker had launched it bore the "As seen on TV" badge, so some serious marketing dollars were put behind this user aquisition feature.

The WebMD offices were impressive, occupying an entire New York City block on Eighth Avenue in Chelsea. The building was massive. I sat all the way in the back, and it was a literal block's walk just to reach the elevator. The brief I received was deceptively simple: build an interactive body map where users could click on body parts to report symptoms, but do it in HTML and JavaScript. But the technical reality was anything but simple. This was 2005. Internet Explorer 6 was the dominant browser, but that didn't mean we could even use those latest specs as so many people were on IE5, or 4 or Netscape. The things we would take for granted just a few years later like PNG transparency support was inconsistent, and that meant we couldn't use it. DHTML, ahem I mean, JavaScript, was still considered "progressive enhancement" and we needed to build something that felt native, responsive, and worked across every browser configuration imaginable.

The Flash version had set a high bar. Smooth hover effects. Instant image swapping. Perfectly positioned popups. Seamless transitions between views. My job was to prove that JavaScript could get close without requiring a plugin. Little did I know that this JavaScript version would not only match Flash's functionality, it would replace it entirely, become featured on WebMD's homepage, and become one of many iterations in the Symptom Checker line that still exists today, twenty years later.

Smooth Interactions

The Flash version had set the standard. Users saw a body outline, hovered over body parts to see highlights, clicked to get popups with symptom information, and could seamlessly switch between male/female and front/back views. Every interaction was smooth, every transition was instant, every popup was perfectly positioned.

My challenge was to recreate all of this in JavaScript:

- Two genders (male/female) with instant image swapping

- Two views (front/back) with seamless transitions

- Multiple body regions (head, chest, abdomen, arms, legs, etc.) with hover highlights

- Sub-regions (the head needed eyes/ears, nose/mouth, head/neck) with expandable popups

- Hover states that matched Flash's visual feedback

- Dynamic popups positioned relative to mouse coordinates, just like Flash

- Cross-browser compatibility that Flash didn't have to worry about

This wasn't just a UI component. It was a complete interaction system that had to feel smooth, load faster, and work reliably across every browser configuration, all without requiring a plugin.

The Technical Architecture

Flash had made this look easy. It could create precise clickable regions, handle smooth image transitions, and position popups perfectly. JavaScript had none of these capabilities natively. I had to build them from scratch.

The solution I built used HTML image maps—a technology that was already considered "old school" in 2005, but it was the only way to create precise, clickable regions on an image without Flash. Each body view had a <map> element with polygon coordinates defining clickable areas for every body part, matching the Flash version's interaction model.

<map name="map_male_front">

<area coords="24,33 41,33 41,47 24,46"

href="javascript:showPart('abdomen')"

onmouseover="mOver('abdomen')"

onmouseout="mOut()"

shape="poly" />

<!-- ... dozens more areas ... -->

</map>

But image maps were just the foundation. The real complexity was in the dynamic image loading system. We needed many body part images organized by gender, view, and color scheme. The JavaScript had to:

- Preload images based on the current selection (male/female, front/back)

- Swap images dynamically when users changed views

- Handle hover states by overlaying highlighted body parts

- Manage the head popup as a separate, expandable component

- Position popups dynamically based on mouse coordinates

The image loading system was particularly clever. Flash could preload images seamlessly in the background. To match that, I built a lazy-loading system that only preloaded the images needed for the current view using my absolute favorite rule-breaking JavaScript function eval():

function loadImages() {

if (strSex == MALE) {

if (strView == FRONT) {

for (i in aryMaleFront) {

strPart = aryMaleFront[i];

eval("male_front_" + strPart + " = new Image()");

eval("male_front_" + strPart + ".src = 'images/" + strColor + "/male_front/" + strPart + ".gif'");

}

}

// ... similar for back view and female

}

}

No, you couldn't just create an Image element on the DOM, not with the browser spec we were targeting. But this approach matched Flash's preloading behavior while minimizing initial load time. When users switched views, the images were already cached, making the transitions feel as instant as Flash's.

PNG Transparency Hell

The popup system was where browser compatibility became a nightmare. Then-modern browsers (IE6, Firefox, Safari) supported PNG transparency, but older browsers didn't. The popup needed rounded corners and a pointer, which required transparent PNGs.

I built a dual-popup system that detected browser capabilities and rendered the appropriate version:

var nua = navigator.userAgent.toLowerCase();

if ((nua.indexOf("msie 6") != -1) || (nua.indexOf("firefox") != -1) || (nua.indexOf("safari") != -1)) {

boxType = PNG;

} else {

boxType = GIF;

}

For IE6, I used CSS filters (filter:progid:DXImageTransform.Microsoft.AlphaImageLoader) to achieve PNG transparency. For other modern browsers, standard CSS background images worked. For everything else, we fell back to GIF versions with solid backgrounds.

The popup positioning was equally complex. The popup needed to appear near the clicked body part, but couldn't overflow the viewport. I calculated the container's position using offsetParent traversal:

function showPart(strPart) {

mx = 0;

tempField = document.getElementById("sym_container");

while (tempField!=null) {

mx += tempField.offsetLeft;

tempField = tempField.offsetParent;

}

document.getElementById("sym_popup_container_" + boxType).style.left = mx-161 + "px";

document.getElementById("sym_popup_container_" + boxType).style.top = my-48 + "px";

}

This ensured the popup appeared in the right place regardless of page layout or scroll position.

The Head Detail View: A Popup Within a Popup

One of the most sophisticated interactions was the expandable head view. When users hovered over the head area, a larger, detailed head popup appeared with sub-regions for eyes/ears, nose/mouth, and head/neck. This required:

- A separate image map for the head

- Coordinated image loading for head-specific body parts

- Smooth show/hide animations

- Preventing conflicts with the main body map

The head container was positioned absolutely and toggled via display properties, with separate image maps that switched based on gender and view:

function showHead() {

document.images["sym_head_bg"].src = eval("bg_" + strSex + "_" + strView + "_head").src;

document.images["sym_head_map"].useMap = "#map_" + strSex + "_" + strView + "_head";

document.getElementById("sym_head_container").style.display = "block";

}

Why JavaScript Won

Looking back, there are several principles that made this JavaScript implementation not just match Flash, but replace it:

1. Solve the Right Problem The Flash version worked beautifully, but it required a plugin. The JavaScript version solved the same user need, making medical information accessible without requiring medical terminology, while eliminating the plugin dependency. This core value proposition never changed.

2. Keep the Interaction Model Simple The Flash version had set the standard with the "click where it hurts" metaphor. By matching that interaction model exactly, users didn't notice the technology change, they just noticed it worked everywhere, without plugins. Simple interactions age well; complex ones don't.

3. Build for Graceful Degradation Flash rendered consistently everywhere it was installed. JavaScript had to work across every browser configuration. By supporting multiple browser capabilities (PNG vs GIF, modern vs legacy), the feature worked everywhere Flash did, plus places Flash couldn't. This broad compatibility meant it could survive browser evolution.

4. Separate Concerns The image loading, popup positioning, and interaction logic were cleanly separated. This modularity made it easier for future developers to maintain and evolve the feature—something Flash's compiled binary made difficult. The JavaScript version could be debugged, modified, and integrated with WebMD's infrastructure in ways Flash couldn't.

5. Performance Matters The lazy-loading image system and efficient event handling meant the feature felt as fast as Flash, even on 2005 internet connections. But unlike Flash, it didn't require a plugin download or installation. Performance is a feature that never goes out of style, but accessibility matters too.

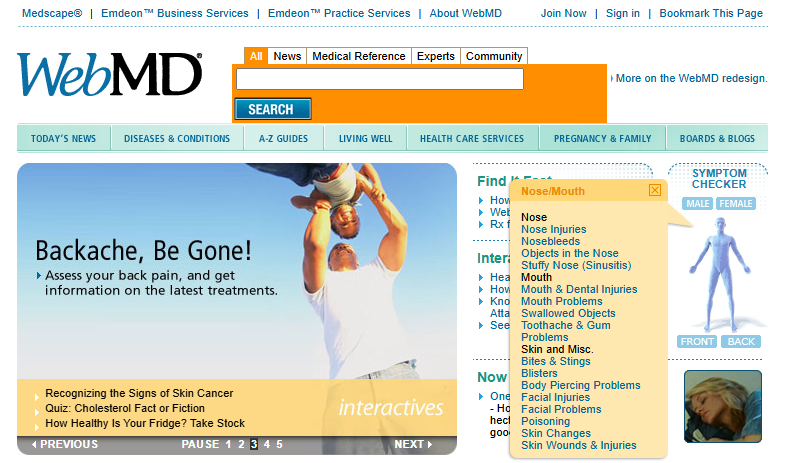

Homepage Hero

The homepage placement was validation that we had successfully matched Flash's capabilities while solving its problems. No plugin required. Better SEO. Easier integration, and it worked everywhere. The visual interaction model lowered the barrier to entry for health information, driving engagement from users who found text-based search intimidating or didn't know the medical terminology for their symptoms. You can still see it working on the internet Archive. Almost. The hilights unfortunatly don't work.

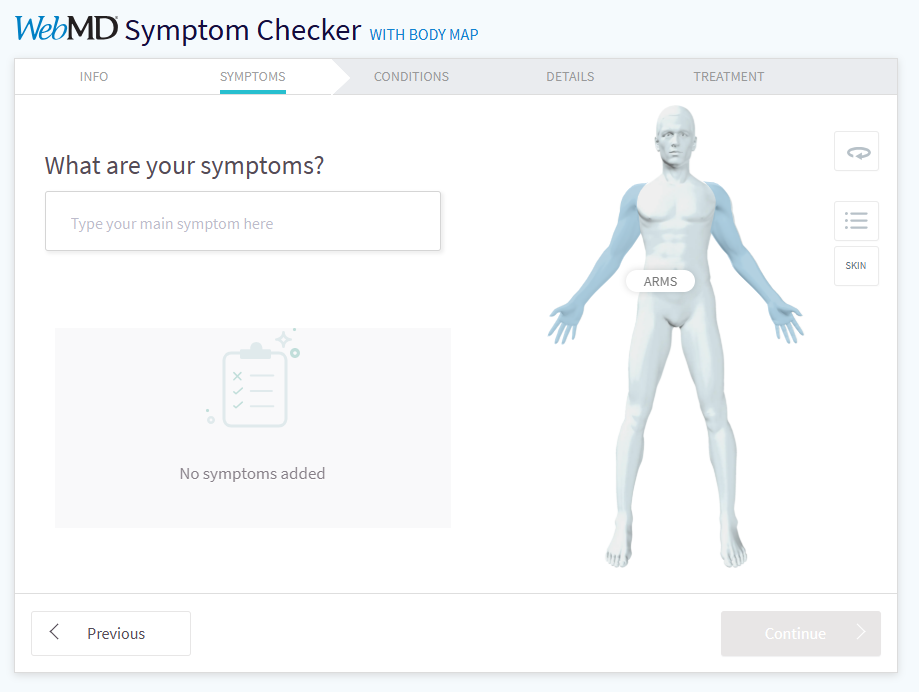

Twenty years later, the core interaction is still the foundation of WebMD's Symptom Checker today. The JavaScript version didn't just match Flash, it replaced it entirely. WebMD featured my implementation prominently on their homepage, making it the primary entry point for millions of users seeking symptom information. According to WebMD's own reporting, it quickly became one of the most widely used tools on the platform during the 2005-2010 period. By 2018, the Symptom Checker was utilized by approximately 75 million people each month.

The feature's success was measurable enough that when WebMD redesigned the Symptom Checker in 2018, they cited user feedback and usage patterns as the driving force behind the update. The redesign integrated a professional-grade diagnostic engine and was informed by feedback from users, medical experts, and academic researchers, including concerns raised in a 2015 British Medical Journal study evaluating the accuracy of symptom checkers. According to WebMD's own history, the body map was removed in that redesign as it focused on text search, but user feedback brought it back. The current version at symptoms.webmd.com includes both the body map and text search, giving users multiple ways to identify symptoms, and bears a remarkable resemblance to the original JavaScript version I built. The fact that it needed to be "redesigned" rather than "replaced" speaks to its foundational role in WebMD's product strategy.

Building a feature that stands the test of time isn't about using the latest technology or following every trend. It's about understanding the user's mental model, solving their problem elegantly, and building something robust enough to evolve. Pretty simple stuff really, just click where it hurts.