In 2005, the idea of an infinite number of songs in your pocket was still a dream. The iPod had revolutionized portable music, but it was a walled garden; you could only listen to what you had already bought (or pirated). Streaming didn't exist. If you wanted to discover music before buying it, you still had to walk into a store, pick up a plastic CD case, walk to a "listening station," scan the barcode, and hope the machine worked. It was a clunky, physical process.

At SapientRazorfish, we were tasked with reinventing this experience for FYE (For Your Entertainment). The goal? Build a "Spotify for the Mall" would be an interactive, touchscreen kiosk where users could browse, search, and preview millions of songs, movies, and games instantly. We weren't just building a website; we were building a physical appliance. What was worse was we had to do it all on embedded Windows CE devices with incredibly low specs, running a custom shell on top of Internet Explorer.

I worked closely with Christian Jungers on the architecture, and what we built was a precursor to the modern Single Page Applications (SPAs) we use today. We were able to apply many of the hard won lessons from my previous work on MusicNet Performer, but this time, we had to adapt them for a touch-based, public-facing kiosk where reliability was even more critical.

The Hardware Constraints

The environment was rough. We were designing for a vertical "poster" format in a busy retail environment.

- Hardware: Low-power embedded PC (Windows CE Embedded).

- Input: A 600x800 portrait touchscreen (no keyboard, no mouse).

- Peripherals: Barcode scanners and magnetic stripe readers (for loyalty cards).

- Network: Slow, unreliable in-store DSL.

Windows CE was a notoriously difficult platform. It was a stripped-down version of Windows that lacked many of the standard libraries and drivers we took for granted on the desktop. We were running on embedded PCs with Geode processors running at 233MHz and a meager 128MB of RAM. The browser wasn't even a full version of Internet Explorer 6; it was a "custom shell" wrapped around the MSHTML.dll rendering engine, which meant we lost many standard browser features.

Standard web page navigation was catastrophically slow on this hardware. A simple page reload could take 4-6 seconds to render, during which the screen would flash white and become unresponsive. For a public kiosk where a user expects instant feedback (like an ATM), this was unacceptable. We realized early on that we couldn't rely on the browser's native navigation at all. We had to build an application that never reloaded. Today, we'd solve this with an SPA framework like React or Vue, dynamically updating the DOM via JavaScript. But in 2005, the IE render engine (Trident) on Windows CE was notorious for memory leaks when modifying the DOM. If you continuously added and removed elements from a single page for hours, the browser's memory usage would balloon until it crashed.

Page reflows were also brutally expensive. On a 233MHz processor, even a small CSS change could trigger a visible "repaint" where you could literally watch the pixels updating from top to bottom. We needed a way to "clean the slate" completely for every new screen while keeping the UI responsive. We weren't just optimizing for speed; we were optimizing for survival. If our JavaScript heap grew too large, the browser process would simply vanish without an error message. Debugging meant connecting over serial cables or hoping your log files survived the inevitable crash.

The Interface

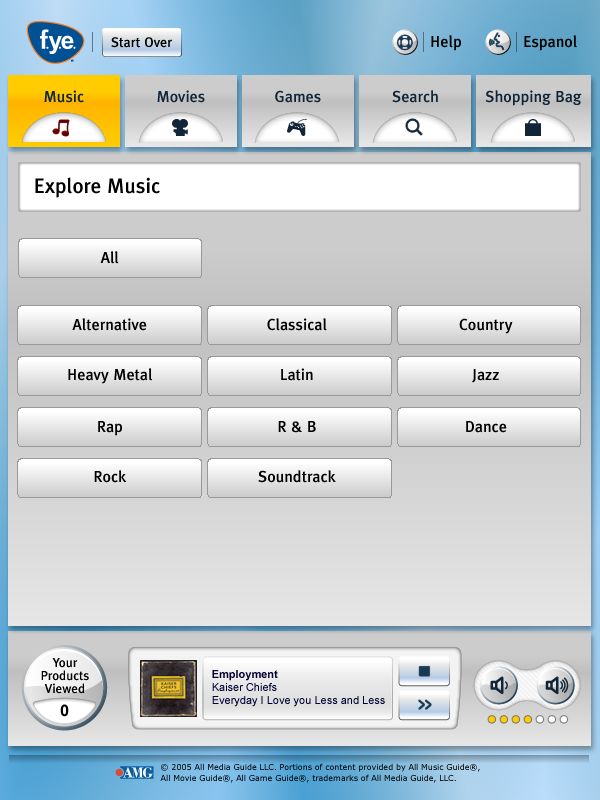

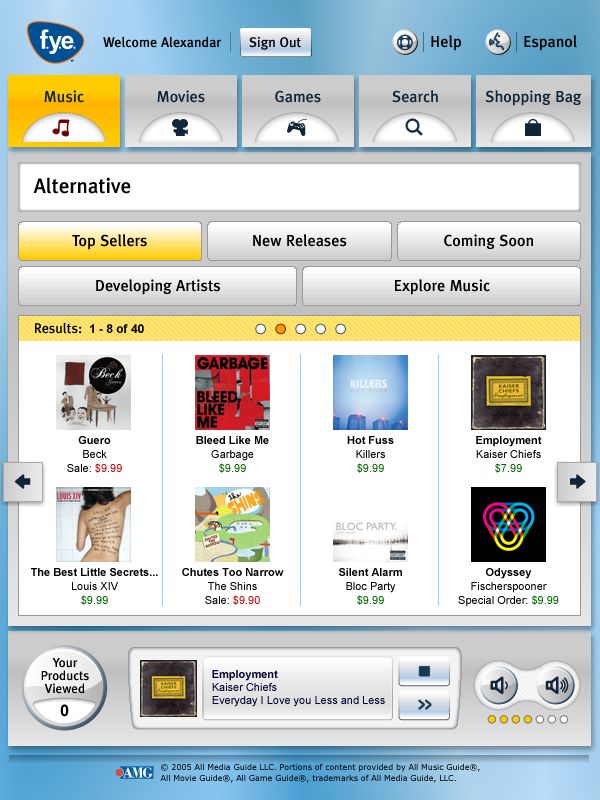

I recently found some screenshots of the actual interface, which brought back memories of the design constraints we were working under.

The UI was designed for fat fingers and impatient shoppers. Notice the massive touch targets and the persistent "Start Over" button. The skeuomorphic "metal" finish wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was a requirement to match the physical casing of the kiosk.

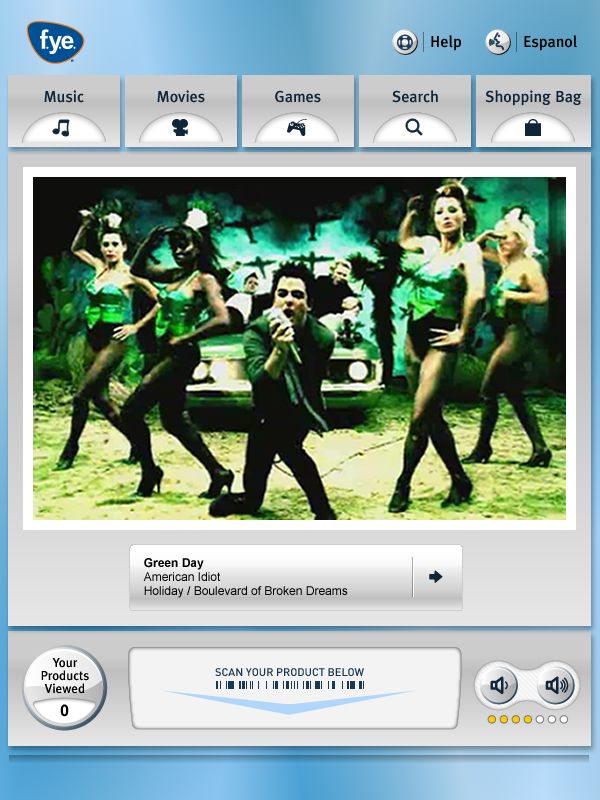

We integrated music videos directly into the browsing experience. This wasn't a separate "video player" page; the video playback was handled by an ActiveX control floating over the web content, controlled via JavaScript.

The "Top Sellers" grid looks simple, but getting this to scroll smoothly on a 233MHz processor was a nightmare. We couldn't use CSS overflow scrolling (it didn't exist). We had to implement custom pagination buttons (left/right arrows) that swapped out the DOM nodes entirely, because scrolling a div with images caused massive tearing and lag.

The "Infinite Stack" Architecture

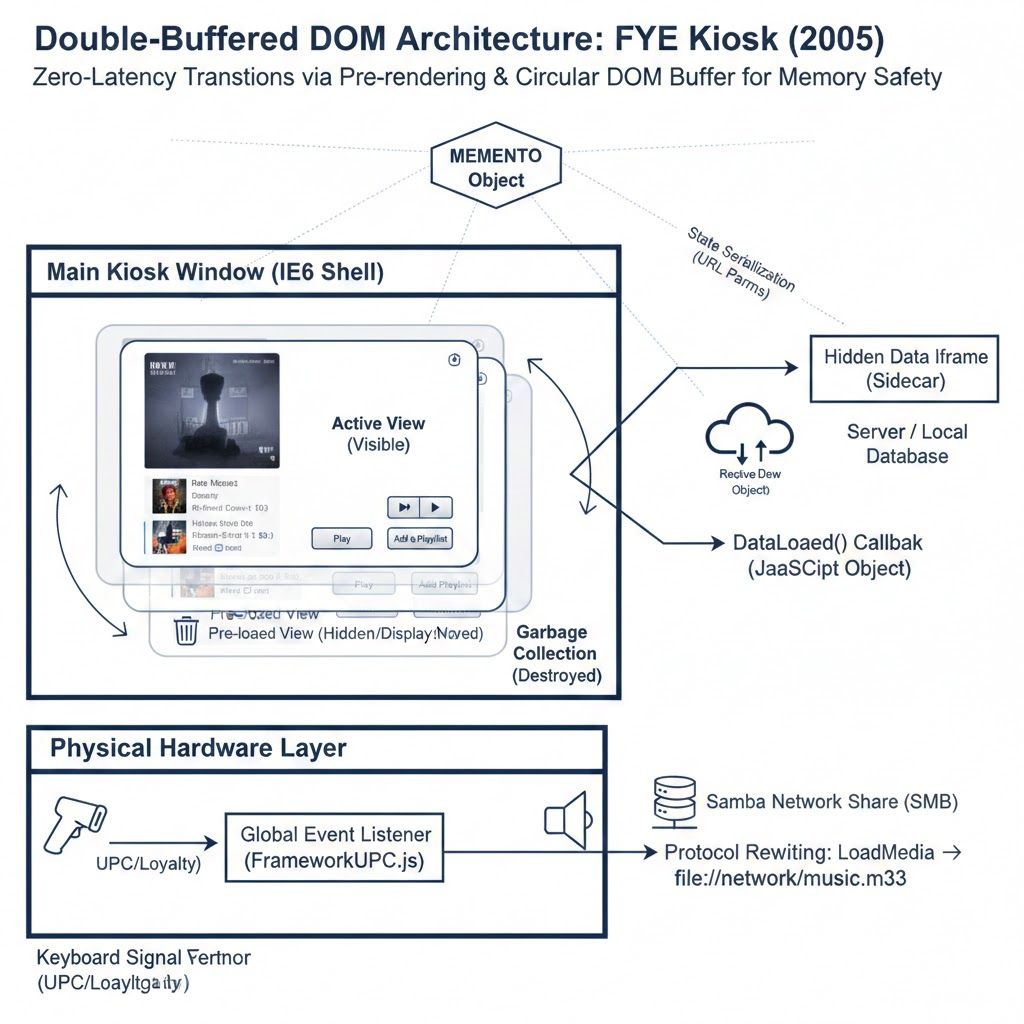

To achieve native-like performance in a browser from 2004, we invented a "Virtual Window Manager" using stacked iframes. By pre-loading the next page in the background while the user was still looking at the current one, we could simulate instant transitions. But as mentioned above, we couldn't just stack them forever; memory was finite. This led to a system that acted like a circular buffer for DOM nodes.

1. Double-Buffering the DOM

We treated the browser like a game engine. Instead of navigating the window to a new URL, we used a Double-Buffering technique.

- When a user tapped a button (e.g., "Browse Rock"), we created a new, invisible iframe in the background.

- We loaded the content into that hidden frame.

- Only when the frame reported it was fully rendered and ready did we swap it to

display: blockand hide the old one.

This eliminated the "white flash" of a page load and made transitions feel instantaneous. To prevent memory leaks on the limited hardware, we implemented a Garbage Collector that would destroy the oldest iframes in the stack once we hit a limit (e.g., 15 frames).

2. AJAX Before AJAX (The "Data Sidecar")

XMLHttpRequest was still experimental and quirky in 2005. To fetch data without reloading the UI, we used a "Sidecar" pattern.

- We maintained a hidden, persistent iframe solely for data.

- To fetch product info, we navigated that hidden frame to a URL like

ControlLookup.aspx?sku=12345. - That page would execute and call a

DataLoaded()function in the parent window, passing back the data as JavaScript objects. - This allowed us to stream metadata, pricing, and inventory levels in the background while the user was browsing.

3. The "Memento" State Machine

Since we weren't doing "real" page navigations, the browser's Back button was useless, but luckily in our kiosk we rand the browser fullscreen so we didn't have to even show the browser's back button. We had to build our own history engine.

We created a global MEMENTO object that tracked the entire state of the application, current user, navigation depth, active playlist, and volume settings. Every time we created a new iframe, we serialized this state into the URL. This meant every screen in our stack was a self-contained "save state," allowing us to implement infinite Undo/Back functionality purely in JavaScript.

Bridging the Physical Gap

The most fun part was breaking out of the browser sandbox. The kiosk had to interact with the physical world.

- The Hardware Abstraction Layer: We built a complete routing engine for physical scans in

FrameworkUPC.js. It wasn't just for products; it differentiated between Loyalty Cards (a specific 12-digit range), Admin Badges (8 digits), Shopping Bags (16 digits), and even "Scan and Win" Tickets. Scanning an admin badge would instantly redirect the kiosk to a hidden/LVS3Admin/portal, effectively logging you into the OS shell with a physical key. - Protocol Rewriting: Streaming audio over 2005-era store DSL was impossible. To solve this, we wrote a custom protocol handler (

LoadMedia) that intercepted generic URLs and rewrote them on the fly to point to local Samba (SMB) network shares. A request for/music/oasis.mp3would be silently converted tofile://network/LocalWeb/music/oasis.mp3, streaming the high-fidelity audio directly from the store's local server. - The "Presence" Monitor: Web apps usually track sessions; we had to track presence. We built an idle loop that monitored physical touch events. If a user walked away, the kiosk wouldn't just log out; it would seamlessly transition into a screensaver mode, playing music videos from a local cache to attract the next customer.

The Legacy

Looking back, the FYE Listening Station was a "React App" built with document.createElement('iframe'). It had component-based architecture, client-side routing, and state management, all hand-rolled in custom JavaScript.

It was a bridge between the physical retail world and the digital future. Today, we just pull out our phones. But for a few years, these glowing touchscreens were the coolest way to discover music at the mall.