In 2025, building a Single Page Application (SPA) is the default. You pick a framework (React, Vue, Svelte), you pull in a state management library (Redux, Pinia), you fetch JSON data from an API, and you render components. It’s a solved problem.

But in 2004, over twenty years ago, none of this existed. There was no React. There was no Redux. JSON hadn't even been standardized (Douglas Crockford wouldn't specify it until the following year). The web was a collection of static pages linked together with full page reloads. The dust had only just settled on the First Browser War, where Netscape and IE fought over the <layer> and <div> tags.

Yet, at MusicNet, we had a mandate: Build iTunes in the browser.

MusicNet was the digital music engine behind major services like AOL Music, Virgin Digital, and others. In June 2003, MusicNet announced the delivery of its entire 350,000-song library via Windows Media 9 Series. To deliver this to users, we needed a client that could stream music, manage downloads, burn CDs, and navigate a massive catalog, all without ever refreshing the page.

It was a "battle line in the sand" for paid music services against the free-for-all of Napster, as noted in this contemporary overview. MusicNet and its rival Pressplay (backed by Sony and Universal) were often derisively referred to as the "Clumsy Twins" by the tech press because of their restrictive rental models. We were trying to sell "expiring music" to a generation used to owning pirated MP3s on Napster forever was hard pill to swallow.

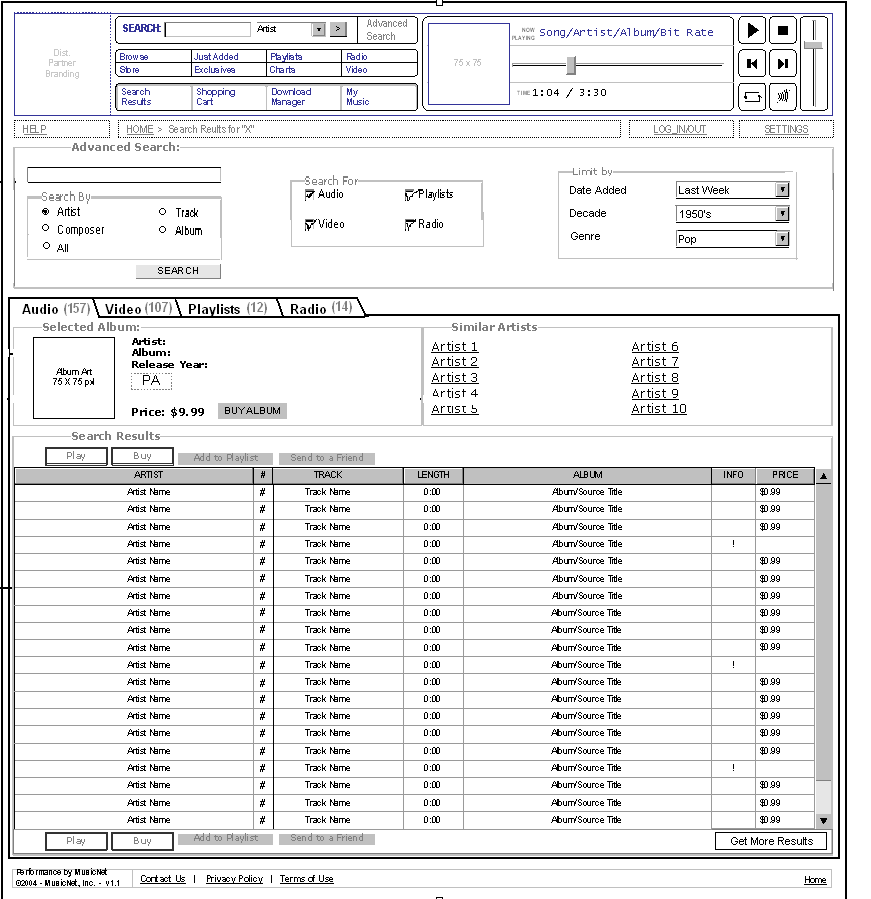

We didn't know it at the time, but we were building one of the world's first complex SPAs. Here is an old wireframe of MusicNet Performer that I found digging through my achives. It kills be that I cannot find an actual screenshot anywhere.

The "Impossible" Stack

To achieve desktop-class functionality in Internet Explorer 6, we had to combine three technologies that hated talking to each other. And we had to do it under legal supervision. Because MusicNet was a joint venture between fierce competitors (Warner, EMI, BMG, RealNetworks), there were reports that antitrust lawyers had to be present in product meetings to ensure the labels weren't illegally colluding. I wasn't just coding against technical constraints; I was coding against a subpoena.

- ActiveX (

PerformerAX): The heavy lifter. Written in C++, this control handled DRM, file system access, CD burning, and the actual audio playback via Windows Media Player. - Flash (

.swf): The UI layer. Since HTML/CSS in 2004 was too primitive for rich interactivity (no flexbox, no rounded corners, no animations), we used small Flash movies for buttons, lists, and players. - JavaScript: The glue. This was the "Controller" that orchestrated everything.

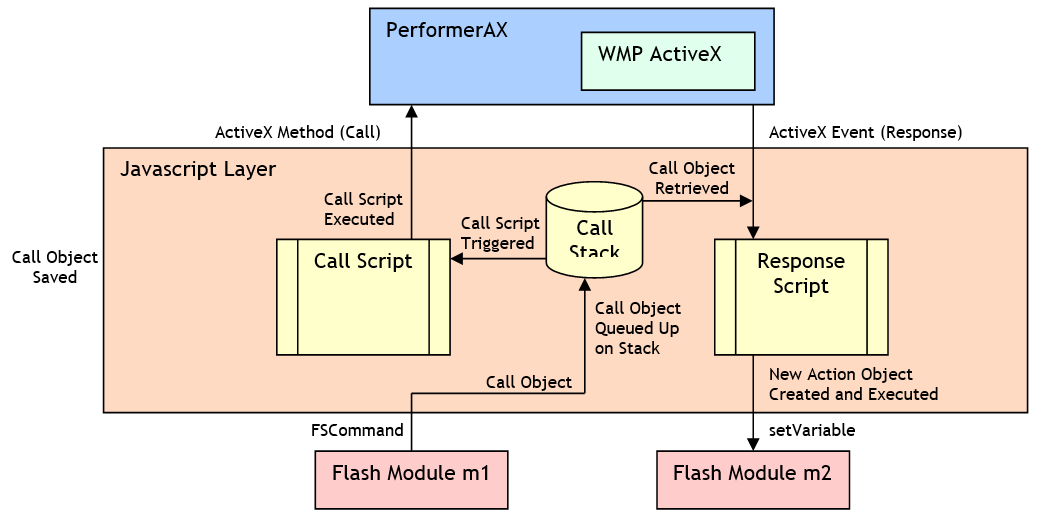

I found these schematics in an old Word doc I had written. This is pre JSON, returning XML from the server rather than raw text was that latest hotness.

The "Proto Redux" Store: PerformerManager.js

The biggest challenge was the "Flash Sandbox." In 2004, Flash had severe limitations. While it could load simple text files or XML, it couldn't easily perform complex, secure transactions with our backend, nor could it speak directly to the C++ ActiveX control that handled the DRM and physical media.

Flash was effectively blind and deaf to the system it was running on. It was purely a display layer.

To get data into a specific Flash module (like the "Featured Artist" box), the module couldn't just fetch() it. It had to ask JavaScript to get it. And since the ActiveX backend was asynchronous, we couldn't just return the value.

I had to invent a full Request/Response Stack and Router.

The Request (The Call Stack)

When a user clicked "Search" in m1.swf (the navigation bar):

- Flash sent an

fscommandto JavaScript: "Search: Oasis". PerformerManager.jscreated aPerformerCallobject, recording who asked (SourceFlashID: 'm1') and what they wanted (Method: 'Search').- This call was pushed onto a Call Stack and marked as

Pending. - JavaScript triggered the ActiveX control to start the heavy lifting.

The Response (The Router)

Sometime later—maybe 500ms, maybe 5 seconds—the ActiveX control would fire an event: OnSearchSucceeded.

But who asked for the search? The ActiveX control didn't know; it just knew a search finished.

The PerformerManager acted as the Router. It would:

- Catch the

OnSearchSucceededevent. - Scan the Call Stack for a pending request that matched this response type (matching the "Search" group).

- Find the original

PerformerCallfromm1.swf. - Execute the specific callback script to push the data back into only that specific Flash instance.

// PerformerManager.js (circa 2004)

function PerformerCall() {

this.SourceFlashID = null; // Who asked?

this.MethodName = null; // What did they ask for?

this.MethodParams = new Array; // Params

this.State = 0; // 0=Pending, 1=Executed, 2=Erroneous

// ...

}

// The "Reducer" / Dispatcher

function mtdProcessResponse(objArgs) {

// ... logic to match the response event to the original pending call

// ... and execute the specific callback script

}

Every action from the UI was wrapped in a PerformerCall object, pushed onto a stack, and tracked. When the ActiveX backend responded (e.g., OnSearchSucceeded), the manager matched the event to the pending call and executed the appropriate logic.

This allowed us to handle race conditions, timeouts, and complex sequences of actions (like "Sign In" -> "Wait for Auth" -> "Load User Library") in a reliable way.

Component Architecture: The Flash Modules

We didn't build one giant Flash file. Instead, we invented a component architecture. The application was composed of dozens of small, independent Flash files (m1.swf through m100.swf).

m6.swf: Featured Artist Componentm9.swf: "Just Added" Listm100.swf: The Main Player Control

These were "dumb" components. They held no business logic. They simply accepted props from JavaScript and emitted events up to the parent.

Props Down (JavaScript to Flash):

// Pushing data into a component

this.GetTargetFlash().setVariable("artistName", "Oasis");

Events Up (Flash to JavaScript):

Flash used fscommand to scream at the browser, which PerformerManager.js intercepted and routed.

JSON Before JSON: Serializer.js

We had a massive problem: Persistence.

If a user spent 20 minutes building a playlist and then hit "Refresh" (or IE6 crashed), everything would be lost. We needed to save the state of the JavaScript application into the ActiveX control (which could persist data to disk).

But there was no JSON.stringify() in 2004.

So, I wrote Serializer.js, a custom recursive object walker that could turn any JavaScript object tree into a string string, and re-hydrate it later. It could also serialize to XML, which was critical as our backend communication was XML based. I have uploaded it to GitHub for posterity, where it sits as a still working ES3 library.

// Serializer.js (circa 2004)

function mtdSerialize(obj) {

if (IsSerializable(obj)) {

this.Data = new SerialData('SrliZe', obj, null);

SerializeAll(obj, this.Data);

return true;

}

// ...

}

This allowed us to implement what we'd now call State Hydration or Hot Module Reloading. We could serialize the entire PerformerManager state, save it, and reload it instantly.

The Performer Object Model

The entire system relied on three core objects that encapsulated the communications process:

PerformerCall: Encapsulated a request from Flash (e.g.,GetDiscography). It stored theSourceFlashIDandMethodParamsand sat on the call stack.PerformerResponse: Encapsulated the asynchronous return data from the ActiveX control.PerformerAction: The vehicle for sending data back to Flash. It mapped the raw data from the response into named variables that the specific Flash module was watching (viasetVariable).

By strictly defining these objects, we could write generic scripts that handled complex data routing without hardcoding every single interaction.

Dependency Injection via Naming Conventions

To keep the code modular, I used a dynamic dispatch system based on naming conventions. Instead of a 5,000 line switch statement, the system looked for functions with specific names based on the context.

If a "Search" action happened in the "Browse" module, the system automatically looked for:

Call_Search_m1_browse()(Most specific)Call_Search_m1()(Module specific)Call_Search()(Generic)

This was a primitive form of Dependency Injection or Polymorphism, allowing us to override standard behaviors on specific pages without touching the core engine.

The Legacy

Looking back at the code now, it's fascinating to see how many modern concepts we had to invent from scratch. We were dealing with:

- Client-Side Routing: Managing "pages" without reloads.

- State Management: A single source of truth for async operations.

- Component Lifecycle: initializing and destroying Flash movies as they scrolled into view.

- Serialization: Persisting complex object graphs.

MusicNet Performer was eventually replaced as web standards evolved, but for a brief moment in the mid 2000s, we managed to deliver a seamless, desktop like music streaming experience inside the most hostile environment imaginable: Internet Explorer 6.

It was a "Single Page Application" before the term existed, built with grit, Flash, and a whole lot of eval().

The Legacy

I spent 9 months perfecting this stack, and it worked. Tens of thousands of users streamed music, burned CDs, and managed their libraries through a browser window that behaved like a native app.l

I cannot find a working screenshot of the application today, but I vividly remember it being inexplicably very very brown. You can still see the ghost of it trying to load on the Wayback Machine, forever stuck waiting for long lost endpoints and an ActiveX control that no longer exists.

For months during development, "Hey Ya!" by OutKast was the only test song we had the rights to work with. I know every single lyric by heart, and to this day, I cannot hear "Shake it like a Polaroid picture" without thinking about asynchronous ActiveX callbacks.

It’s easy to look back at the era of ActiveX and Flash with a shudder, but the constraints forced us to innovate. We weren’t just building a website; we were trying to break the browser out of its document viewing prison, and in doing so, we stumbled upon the architectural patterns—state stores, component trees, and asynchronous event loops that would define the next two decades of web development.

As for MusicNet itself? It was eventually sold to Baker Capital in 2005, rebranded as MediaNet, acquired by SOCAN in 2016, and finally sold to Audible Magic in 2021. I vividly remember us trying to sell the platform to Tower Records at one point. That went about as well as Tower Records did, and alas the code I wrote is long gone.

Ironically, after Napster was sued into oblivion (thanks Lars), the "new" legal Napster brand actually ended up using MusicNet's backend to power its legitimate service for a while. The enemy eventually became the customer.

Today, we have npm install react to solve these problems. But back then, all we had was document.all and a whole lot of hope.